The information below has been compiled from a variety of sources. If the reader has access to information that can be documented and that will correct or add to this woman’s biographical information, please contact the Nevada Women’s History Project.

At a Glance:

Born: February 10, 1943, Eureka, California

Died: June 1, 2023, Reno, Nevada

Maiden Name: Weymouth

Ethnicity: English-Irish-German

Married: Howard Griffith “Griff” Durham

Children: Matthew G. Durham 1969,

William H. Durham, 1973

Primary Residences: San Francisco, Calif.; Reno, Washoe County, Nev.

Major Fields of Work: Art Historian, Artist, Local and National Collaborator

Other Role Identities: Community Advocate, Storyteller, Museum Docent, Teacher

Activist, artist, historian created Underfolk

Kathleen Durham was one of thousands of women trailblazers across the country whose dedication to causes beyond themselves contributed to the culture of their families, communities and country.

The infant daughter of Margaret Neagle Weymouth (1911-1991), a teacher, and Lewis Albert Weymouth (1909-1962), a highway engineer, Kathleen was born in Eureka, Calif. in 1943. She was a sister to Bill and granddaughter to Mary (Heinsdorf), when the family moved from Eureka, Calif., to San Francisco, Calif.

Everything changed when she was 5 years old: her brother, Bill, was diagnosed with infantile paralysis, or polio as it was called. Shortly after, Katheen contracted the illness, which became a national epidemic when many children lost their lives. The San Francisco hospitals were full, and a doctor taught Margaret to exercise her children’s limbs and make hot packs to continually press over them, in accordance with the new Sister Kinney therapy treatment. Margaret moved a wringer washing machine into their kitchen and made hot packs all day and Grandmother Mary prepared meals and taught her granddaughter to sew tiny creatures. Margaret theatrically taught her that everything in the house was alive — the toaster and the vacuum, for instance — all had names and personalities. Their parents installed a great dollhouse and Kathleen concocted stories about her little creatures living there — activities that played a large role in her future.

The children recovered but never gained complete control of one leg. Kathleen had some setbacks in high school; one being that, due to polio, she was always the last girl picked for athletic endeavors. The art teacher claimed she had no talent; devastated, she stopped creating anything until many years later, after her sons were born. But she forgot these disappointments after becoming editor of the school newspaper and volunteering at Laguna Honda, a non-profit, publicly funded hospital rehabilitation and nursing home, described as “for the very poor, the very sick, and the very disabled.”

In 1960 she enrolled at the University of California, Berkeley, majoring in journalism and, later, art history, and there met “Griff,” Howard Griffith Durham. One afternoon on campus the two of them heard President John F. Kennedy speak about the Peace Corps he had recently established by executive order to assist other countries in their development efforts by providing skilled workers in certain fields. Accompanying Kennedy was his brother-in-law Sargent Shriver, a driving force behind the creation of the Corps and its first director. They presented such a riveting picture of possibilities that Kathleen and Griff resolved to enlist.

“Those were idealistic times,” she said. “We believed in serving.” The two of them married on January 27, 1963, in Santa Barbara, Calif., and after Griff’s graduation they began Peace Corps training. They were sent to the Brazilian state of Ceará where Griff mentored a Heifer Project program that gave out purebred swine to families, and Kathleen taught sewing and participated in a midwives’ program. What a pleasure it was to see a young midwife using the kit she had been given to tie off the umbilical cords of the piglets. After two years, the couple returned to the United States and worked to train new recruits to the Corps.

They headed to Los Angeles, and en route stopped to vacation with Griff’s family in Redwood City, Calif. While there, they manned a table to collect signatures protesting the transport of napalm through town. Kathleen sewed Huelga flags (Huelga translates to “strike” in English) and picketed Safeway for farm workers’ rights.

They traveled to Los Angeles and the University of California at Los Angeles where Griff did graduate work, and Kathleen continued her studies of art history. Her pregnancy made the couple realize they didn’t want to raise children in Hollywood and in 1969, when Griff was invited to be a research assistant at the University of Nevada-Reno (UNR), working with Dr. Mary Rusco on an Inter-Tribal Council Communications project, they headed to Nevada, stopping along the way in San Francisco, where Matthew was born. In Reno, both went to work, Griff at UNR and Kathleen at the Inter-Tribal Council’s youth craft program at the Reno-Sparks Indian Colony in Yerington, Wadsworth, and Carson City. She discovered the resources of the Downtown Reno Library. Through all these moves and changes, she kept busy with her stitchery and invented witty stories to accompany whatever she made.

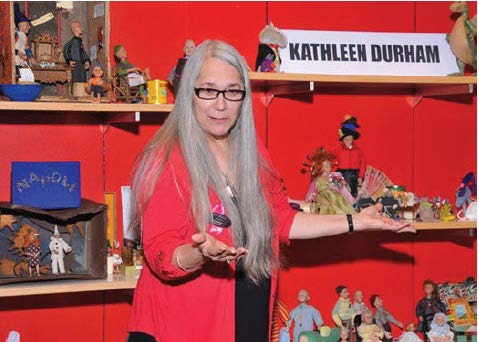

After Will was born, Kathleen began to sculpt and sew and began creating little people. “Grandpa Troll was the first one I made. When I had his little head in my hands, I realized I had actually made something out of clay — it was amazing.” Her clay people with their hand-sewn outfits and whimsical and captivating stories took shape. She called them the “Underfolk,” and they lived under her house, in “Underwood.”

L-R: Mama Windex with baby Comet, Papa Drano, Nosalie Marie, Gramma Brillo, Uncle Lysol and Grampa Pete Trap, with their finest dish rag.

Photo by Susan Mantle, from Wild Women Artists website.

At the library she organized a storytelling series for the children but was later un-invited because she lacked official training. She was a founding member of the Friends of the Library and became its president.

Her involvement with the national AIDS Quilt Project brought together people whose family and friends had died of AIDS. They made quilt squares with a personal touch, each commemorating the name of a dear person lost to AIDS, and Kathleen assembled them into a 3’ x 6’ panel, which was exhibited at the Washoe County Fairgrounds. In 1987 it was sent to join thousands of other panels at the National Mall in Washington, D.C. Today, the AIDS quilt weighs 54 tons and can be viewed online at Interactive AIDS Quilt.

In 2008, interested in politics, she cooked vegan and regular dinners for the Obama Reno campaign headquarters, every Thursday night during the election season, and with Griff, she ran the caucus for their precinct. She repeated the gesture for Rory Reid’s unsuccessful campaign for governor in the 2010 election.

Kathleen’s work life was interwoven with her volunteer activities. For instance, she was director of activities at a local memory care home because of her experience with her mother’s Alzheimer’s disease. One day she was making Cornish pasties with the group and one woman, who had not spoken for years, spoke up and admonished, “Let it steam!” When the company replaced Kathleen with a 22-year-old “expert,” (Griff’s description) she continued as a volunteer. She designed and stitched quilted tops and jackets to sell at Reno specialty stores. Once she soft-sculptured small animal creatures around a large, quilted blackjack table; a Harold’s Club executive bought it. She offered support to the Holland Project, a non-profit arts organization for young people, and also worked at Rancho San Rafael’s Wilbur D. May Museum.

Kathleen continued creating her “Underfolk.” We learned about “Onion Ed, who cried on behalf of those who needed it. He wasn’t sad, he was just good at crying. We saw a dented antique teapot as a home for Earl Grey and his wife Jasmine,” she explained. “Plans for a large Underwood library are underway, and tweets have been sent out (by bird) advertising for a librarian. In the meantime, Mr. Punch has been busy getting the books catalogued. He isn’t very efficient. He reads and reads, but I haven’t seen much organizing going on.”

After the new Nevada Museum of Art was built in 2003, Kathleen became a volunteer, then a docent, speaking to and educating patrons. Next, fascination and curiosity brought her to the museum’s research branch, where she used her academic background in art history to bring to light previously unknown information on exhibitions and collections.

She joined the Wild Women Artists, a small but mighty group of Nevada professional artists working in a variety of media who come together twice each year in Reno and Elko to show and sell highly regarded works of art. Kathleen located various venues, such as Rancho San Rafael and Summit Mall, where Wild Women shows opened at various temporarily-closed stores. The Wild Women’s guiding words came from author Clarissa Pinkola Estés: “Within every woman there is a natural creature, a powerful force filled with good instincts, passionate creativity and ageless knowing. Her name is Wild Woman.”

Photo by Susan Mantle

Her reputation grew. Underfolk stories were in demand and attracted adults and children alike. She offered performances for cultural and civic groups, including Nevada Women’s History Project, Nevada Museum of Art, and others. She brought her Underfolk to the museum on Family Saturdays once again, entrancing children and their parents, and she became an art historian. She was a featured artist in Women Artists of the Great Basin by Mary Lee Fulkerson and Susan Mantle.

Claire Muñoz, vice president of museum advancement and deputy director of NMoA, wrote, “Kathleen was a docent, volunteer, and storyteller at the Museum for more than twenty-five years. She conducted meaningful research on the Museum exhibitions, collections and history that we continue to reference today. She was involved in the annual Scholastic Art Awards, a national art competition for middle school and high school students that the Museum has administered since 1999. Kathleen served as a juror and would help identify and recommend young talent for the awards. Each year, she would select one female emerging artist as the recipient of the Wild Women Scholarship.”

Kathleen passed away in 2023, of cancer. Muñoz wrote, “As the Museum learned of her failing health, we decided to honor her legacy by working with Katherine Case, of the Wild Women Artists to rename the scholarship in her honor. The Museum committed to matching the funds raised by the Wild Women increasing the size of the scholarship from $500 to $1000 annually. The scholarship is now called “The Kathleen Durham Wild Women Scholarship.” We honor Kathleen at the Scholastic Art Awards Ceremony as the scholarship is gifted to one special student.

In order to maintain the scholarship in perpetuity, the Wild Women hosted a fundraiser after Kathleen’s death. As a result of the fundraiser and additional gifts from friends and family of Kathleen, the scholarship fund raised more than $16,000 to support young female artists in the region.

After her death, Kathy was cremated, and her ashes were scattered in locations significant to her life.

Researched and written by Mary Lee Fulkerson, with assistance from Griff Durham; Claire Muñoz, Jimmie Benedict, Wild Women Artists founder; and Elisa Brown, Washoe County Library staff.

Posted December 30, 2024

Sources of Information

Ancestry.com. Year: 1950; Census Place: San Francisco, San Francisco, California; Roll: 5538; Page: 18; Enumeration District: 38-1184. [Kathleen Weymouth]

“Docent shares joy of artwork. Volunteers get visitors to ‘look’.” Reno Gazette-Journal (Reno, Nevada) 3 June, 2011, p. 29, 30.

“Durham-Weymouth Rites Solemnized at Newman.” The Berkeley Gazette (Berkeley, California). 2 March, 1963, p. 3.

Fulkerson, Mary Lee. Photographs by Susan E. Mantle. Women Artists of the Great Basin. University of Nevada Press: Reno, Nevada. 2017

“Kathleen Durham, handsewn whimsies.” Reno Gazette-Journal (Reno, Nevada). 10 December, 1990, p. 17.

“Tales from under the sink.” Reno Gazette-Journal (Reno, Nevada) 5 November, 2008, p. 21, 26.