The information below has been compiled from a variety of sources. If the reader has access to information that can be documented and that will correct or add to this woman’s biographical information, please contact the Nevada Women’s History Project.

Photo courtesy of Dianne Jennings

At a glance:

Born: March 24, 1956, Modesto, Calif.

Died: July 19, 2007, Reno, Nev.

Maiden Name: Woody

Married: 1) previous marriage, Aug. 24, 1980, divorced;

2) Angus Robert Quinlan, Aug. 28, 2004.

Children: Chris Woody

Primary cities and counties of residence and work: Carson City; Minden, Douglas County; Reno, Washoe County; Las Vegas, Clark County.

Major fields of work: archeology, co-founder and executive director of Nevada Rock Art Foundation

Archeologist spearheaded documentation of state’s rock art

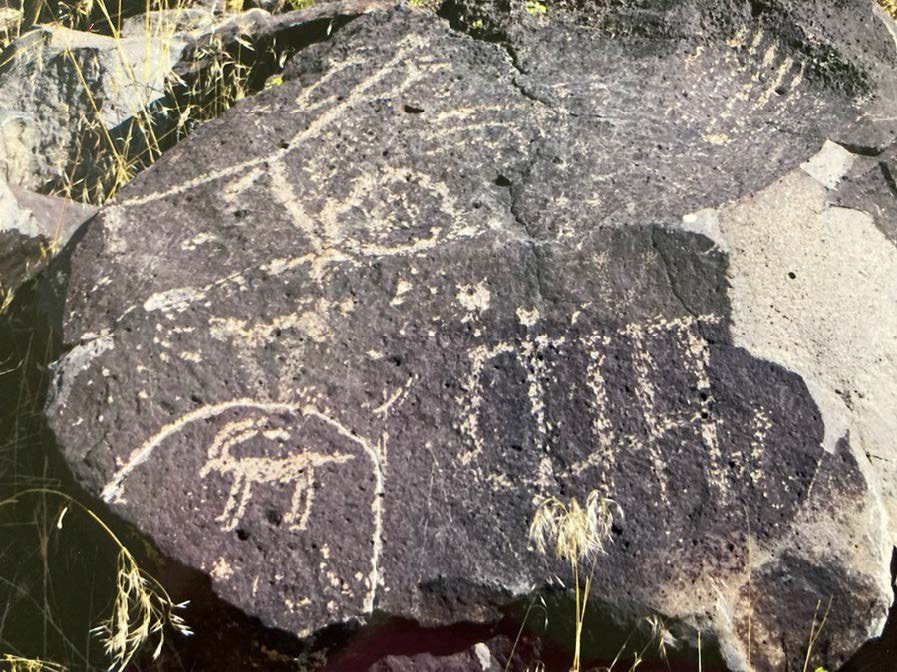

Alanah Jean Woody, an archeologist educated and trained in Nevada and England, was a crusader to raise awareness and protection of ancient rock art in Nevada and in her scientific field. She co-founded the Nevada Rock Art Foundation and led a corps of volunteers in documenting petroglyphs and pictographs across Nevada.

Born in Modesto, California, on March 24, 1956, Woody was the daughter of hard-rock miner and tunnel engineer H. Eugene Woody and Lola Stockman Woody. The family, including her brothers Dwight and Duane, lived in Pakistan and the Dominican Republic in her childhood. These travels fostered an interest in other cultures which may have led to her interest in anthropology as a career.

Woody worked as a clerk in the Carson-Tahoe Hospital emergency room in the late 1980s-early 1990s where she met Joan Johnson, an ER nurse, from Virginia City. Years later she convinced Johnson to be the site steward for the Lagomarsino Canyon rock art site in Storey County, Nev.

By 1996, Woody had earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in anthropology at the University of Nevada, Reno, studying under Professors Donald and Catherine Fowler. She served as teaching assistant to Dr. Eugene Hattori and as field school director of the Warner Valley project in Lakeview, Oregon.

Woody was one of a small group of women who had returned to the university in their 30s, said Darla Garey-Sage, who also earned anthropology degrees at UNR at the same time. Woody was exceptionally dedicated to the study of archeology. “She was very motivated and passionate, totally focused and knew what she wanted to do.”

Finding her passion for rock art

On an archeology field trip, Woody visited the Massacre Lake rock art site in northern Washoe County and became fascinated, changing her focus from a standard settlement approach over to the study and preservation of rock art.

For her master’s thesis, Woody explored the sequencing of layers superimposed on one another within rock art panels, Catherine Fowler said. She postulated that there were a number of succeeding stages and that the rock art had been executed in different styles by multiple groups of artists. This site offered a unique opportunity to make these observations.

“She was part of an era, she read all the literature and attended meetings,” according to Catherine Fowler. The era included new thinking and research by women archeologists like Polly Schaafsma of New Mexico.

Woody continued her education and research at the University of Southampton in England from 1996 to 2000, earning a Ph.D. degree in 2001. She found new ideas and more techniques by studying rock art from Australia and South Africa, Don Fowler said.

In graduate school she met her future husband, Angus Quinlan, who followed her to Nevada. They married in Las Vegas in 2004.

Beginning in 2001, Woody worked again with Dr. Hattori, curator of the anthropology department of the Nevada State Museum in Carson City, as the Collections Manager. “She hit the ground running,” Hattori said. “She was responsible for revamping the 7000 square foot warehouse, field work, and the remodel of the basketry vault.”

Hattori and Woody were co-curators of the museum’s Under One Sky exhibit that opened in 2002. She was also the lead co-curator of a series of native American art exhibitions, and she selected paintings and sculptures for purchase for the museum collections.

She taught introductory courses in anthropology, archeology, world history and prehistory rock art at Western Nevada Community College and at Sierra Nevada College in Incline Village.

Woody, with co-founder Shari Chase, of Chase International Real Estate, incorporated the Nevada Rock Art Foundation in January 2002. “Her passion illuminated everyone around her,” Chase said.

Chase and Woody decided that the best way to raise money and to secure grants to fund programs was to establish a foundation. Chase funded the initial start-up, recruited board members like attorney Tom Hall and sought sponsors for the successful “Adopt a Petroglyph” program. “I was proud to be part of Nevada history that was not documented,” Chase said.

Recruiting an army of volunteers

Woody left the museum in 2006 to become the foundation’s full-time executive director. Her enthusiasm attracted a pool of about 300 volunteers, half of them working at least two days total time. The most dedicated workers, between 50 and 75 volunteers, repeatedly signed up for the task of documenting sites, especially those threatened by climate, vandalism, or nearby development.

Her signature project was recording more than 2,200 rock art panels in the Lagomarsino Canyon site, one of the largest in the state in terms of rock art abundance. Other sites recorded include Mount Irish and Little Red Rocks in southern Nevada.

She had a talent for making everyone fall in love with rock art and tapped into each volunteer’s skills and interests. Woody relied on Ralph Bennett of Reno Artists Co-op Gallery to draw site area overviews; Cheryln Bennett trained volunteers on site description forms, which were later input into the international IMAX program. Teri Ligon of Carson City labelled slides with her precise printing. Other volunteers organized office help, events and fundraisers and designed tee shirts. Jeff Thelen of Truckee, Calif., a former city planner and geographer, was given the task of managing the first recording session of Crow’s Nest site in Washoe County.

“Alanah trusted that when she gave me a job, I would get it done,” Thelen said. He provided “creature comforts” to motivate and retain volunteers. “I started making salads and brownies so they would have energy after lunch.”

Thelen saw how Woody improved recording techniques. “We made measurements, took orientations and mapped locations of the glyphs.”

In southern Nevada, Woody enlisted Elaine Holmes and Anne McConnell of Las Vegas who put together a cadre of volunteer documenters in sites at Grapevine Canyon, Gold Butte, and Lincoln County.

“Alanah was able to captivate anyone’s interest in rock art with her enthusiasm, knowledge and ebullient personality,” Holmes wrote. “She was a terrific friend and leader.”

“I had taken drafting and architecture in school,” said Carolyn Barnes Wolfe of Sparks. She first offered to cater lunch for a crew of volunteers at Lagomarsino Canyon. After lunch, Woody conducted a tour of the site. “I was totally ecstatic about the art and wanted to be part of the adventure.”

Finetuning the business of documentation

Woody enlisted Barnes Wolfe in refining a technical key to guide volunteers in recording rock art, building on procedures developed by Jane Kolber. Barnes Wolfe found that many early drawings were unclear and had arrows and written comments on them, making them too busy and hard to read.

Woody adapted standard archeological field techniques to the recording of rock art panels, using a flexible string grid taped to the surface of the rock. She taught volunteers to use distinct representations of the techniques used by the original artists, such as stippling, solid lines, superimposed images, and scratching. The drawing key had symbols for features unique to rock art, such as bullet holes, spray paint, graffiti, rock scrapes, lichen, cupules, pecking and milling surfaces.

Woody instructed the volunteer recorders to “draw what you see, not what you think it means.”

Woody’s work with other agencies established uniform recording procedures for all rock art sites in Nevada, Pat Barker said. He was the Bureau of Land Management’s State Archeologist for Nevada from 1988 to 2006; he became chairman of the Nevada Rock Art Foundation board from 2009 to 2012.

Making rock art relevant to archeology

“She put Nevada rock art on the map,” Catherine Fowler said, expanding the significance of rock art for general archeology. “Archeologists didn’t know what to do with it [rock art]. They saw it as doodling or fringy,”

“Early interpretations of rock art were impressionistic,” said Darla Garey-Sage, often based on observers’ personal understanding of the meaning of the imagery and symbols. Woody and Quinlan instead instituted systematic, data-driven analysis, using motif counts, objective descriptions of images and a formal system of recording rock art.

“Alanah wanted to figure out why the rock art was where it was, which would give us more information about habitation sites and camp activities. She and Gus (Quinlan) were leaders in scholarly contextualism of rock art into archeology theory and practice.”

“She made people change their thinking and understand that rock art is not all hunting magic,” said Renee Kolvet, also an archeology graduate student who shared an apartment with Woody.

“What Alanah and Gus taught us is that we should look at rock art as part of the entire archeological record, not in isolation,” explained Geoffrey Smith, Regents’ Professor of Anthropology and Executive Director of the Artemisia Archaeological Research Fund, University of Nevada, Reno.

Woody sometimes differed from popular or scholarly theories about the meaning of rock art, Hattori said. “She did not always agree with the ceremonial or religious interpretations of male-centric shamanism.”

Some rock art may be related to women’s activities, Woody believed, and the discovery of vulval forms in and around domestic campsites led her to believe they were indicative of female ceremonies of fertility or childbirth.

Programs to preserve Nevada rock art

To keep rock art sites as intact as possible, Woody inaugurated a pilot program of stewardship for the Dry Lakes area in northern Nevada in cooperation with the Bureau of Land Management’s Carson District Office.

Although controversial for the time, a key initiative of Woody’s vision was introducing the public to rock art through regularly scheduled tours of two public sites, Grimes Point near Fallon, and the Valley of Fire in southern Nevada. Her purpose was to encourage appreciation and to teach better site etiquette.

She launched a series of public lectures in Reno, one given by world-famous archeologist Paul Bahn. She prepared cultural site materials for Lincoln County schools. She designed a plan for interpretation of extensive field recordings. Woody was full of energy and enthusiasm. “She was the Pied Piper, the Energizer Bunny,” Don Fowler said.

Her intensity stemmed from her view that rock art is vulnerable to time and constant erosion. “She felt strongly that her mission was to record the rock art before it was lost,” Hattori said. “Once recorded, she advocated for protection and additional study.”

Woody died following a short illness in Reno on July 19, 2007. Her untimely death did not stop the efforts she began. Her husband, Dr. Angus Quinlan, and dedicated volunteers continue her work, including documentation of petroglyphs at Lahontan State Park in September 2014.

Researched and written by Janice Hoke. Posted February 21, 2024.

Sources of Information:

- Ancestry.com, California Birth Index; 1905-1995 [database on-line] Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2005. [Alanah J. Woody]

- Ancestry.com. California, U.S., Marriage Index, 1960-1985 [database on-line]: Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2007. [Alanah Jean Smith].

- Ancestry.com, Nevada, U.S. Divorce Index; 1968-2015 [database on-line]: Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2007. [Alanah Jean Smith]

- Ancestry.com. Nevada, U.S., Marriage Index, 1956-2005 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2007. [Alanah Jean Woody]

- Barker, Pat, Personal interview, 28 June 2023.

- Chase, Shari, Telephone conversation, 24 Sept. 24, 2023.

- Fowler, Donald & Catherine, Personal interview, 26 July 2023.

- Garey-Sage, Darla, Personal interview, 10 Aug 2023.

- “Winter Graduation at University.” Reno Gazette-Journal; (Reno, Nevada), 8 Dec 1996, “Graduation” continued pg. 8-9C.

- Harmon, Mella Rothwell. (2007). In Memoriam: Alanah Woody (1956-2007). Nevada Historical Society Quarterly, 361. Retrieved from https://epubs.nsla.nv.gov/statepubs/epubs/210777-2007-4Winter.pdf

- Hattori, Gene, Personal interview, 28 June 2023.

- Holmes, Elaine, Email, 24 Sept. 2023.

- Kolvet, Renee, Personal interview, 6 Sept. 2023.

- Quinlin, Angus. “Nevada Rock Art Foundation Mourns the Passing of its Co-Founder and Guiding Light”, Fall 2007. Digital. Accessed on 15 Jan. 2024. https://www.nvrockart.org/text_files/newsletter_files/GN_6_4.pdf

- Quinlin, Angus, Personal interview, 25 May 2023, 16 Oct 2023.

- Smith, Geoffrey, Personal interview, 15 Aug. 2023.

- Wolfe, Carolyn Barnes, Personal interview, 14 Sept & 15 Oct. 2023.

- Woody, Alanah. “Resume,” 1989-2007.