The information below has been compiled from a variety of sources. If the reader has access to information that can be documented and that will correct or add to this woman’s biographical information, please contact the Nevada Women’s History Project.

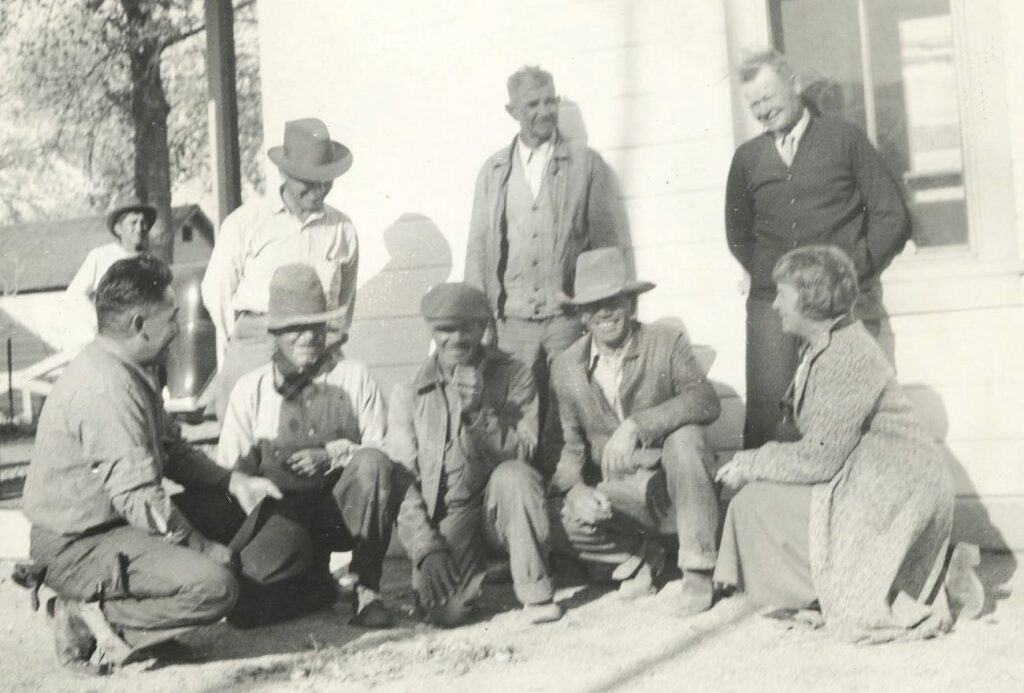

Photo from the Nevada Historical Quarterly, 1982. Courtesy of Edward C. Johnson

At a Glance:

Born: November 29, 1887, Moro, Illinois

Died: May 17, 1968, Riverside, California

Maiden Name: Bowler

Ethnicity: Caucasian

Primary Residences: Alton, Illinois; San Francisco, California; Stewart Indian School (Carson City), Nevada; Glendale and Riverside, California

Burial Location: Forest Lawn Cemetery, Glendale, California

Major field of work: Social work, Federal government administration (Children’s Bureau and Indian Service)

Other role identities: High school English teacher, Red Cross worker

Biography:

First female U.S. Indian agency head advocated for

Native Americans in Nevada

Alida C. Bowler was a trailblazer who crossed gender boundaries throughout her career. Her legacy began at the University of Illinois, where she graduated in 1911 with significant honors and two psychology degrees. “By all accounts, Alida Cynthia Bowler, psychology graduate of the University of Illinois in 1910 and 1911, was an extraordinary woman,” says Angela Jordan of the University of Illinois Archives. Fresh out of college, she entered the workforce during the height of the Progressive Era when American women had taken the lead in social, moral, and economic reforms.

Alida Bowler is the daughter of Benjamin H. and Caroline (Peers) Bowler. Bowler never married but spent a lifetime serving others.

Bowler’s education and life experiences would prove invaluable. She taught English at her home high school and was a psychology instructor at Ohio State University when America entered World War I. She served in the American Red Cross when female social workers were sorely needed. After the Armistice, she helped clothe, feed, and resettle refugees in Romania during the Russian civil war. She returned to the States in September 1919 and continued to work for the Red Cross in Seattle, Washington.

Bowler’s introduction to Indian advocacy began in the mid-1920s when she was hired as executive secretary of the San Francisco office of the American Indian Defense Association (AIDA). She spent five years studying the plight of California Indians while national executive secretary John C. Collier was on a national campaign to reform misguided federal Indian policy that had led to massive losses of Indian land, forced assimilation, and threats to Indian culture and religious freedom.

Bowler eventually went to work for the City of Los Angeles — first as secretary to the police chief and later as director of public relations. After a few years she was called back to social work. As the director of the delinquency division of the United States Children’s Bureau in the early 1930s, she studied juvenile delinquency and the state of children’s facilities. Her co-authored study, “Institutional Treatment of Delinquent Boys,” is still referenced today.

Bowler continued to stay abreast of Collier’s fight to repeal Indian policy and enact new legislation. A modified version of the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) was passed on June 18, 1934. The merger of the IRA and the president’s massive legislative and executive initiatives was known as the Indian New Deal.

But passage of the new law was just the beginning. The IRA was predicated on the tribes electing tribal councils and adopting constitutions and by-laws. As Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Collier needed field superintendents like Bowler at the rural Carson Indian Agency in Nevada and eastern California to educate the tribes on the IRA’s benefits. Its native population included 6,000 Washoe, Paiute, and Shoshone Indians, many of whom lived off-reservation, on the fringes of towns, mines, and ranches. The agency also operated the Carson [Stewart] Indian Boarding School.

At 48 years old, Bowler became the first female Indian agency superintendent in history. She was appointed on September 1, 1934. She and her housecats moved into the superintendent’s house at the agency headquarters at the Carson Indian School. In a 1934 New York Times interview, Collier defended his selection of a female superintendent: “There should be many more women in such positions. There is precedent among the Indians themselves. Iroquois women were leaders in women’s suffrage. In many tribes, women have leading positions.”

Bowler was actively involved in Indian School programs when she wasn’t visiting distant reservations or attending national meetings. She and her staff traveled thousands of miles over dusty, rutted roads to meet with leaders of the 11 reservations and 9 colonies. Bowler established strong relationships with most tribes, and all but two adopted the IRA during her tenure.

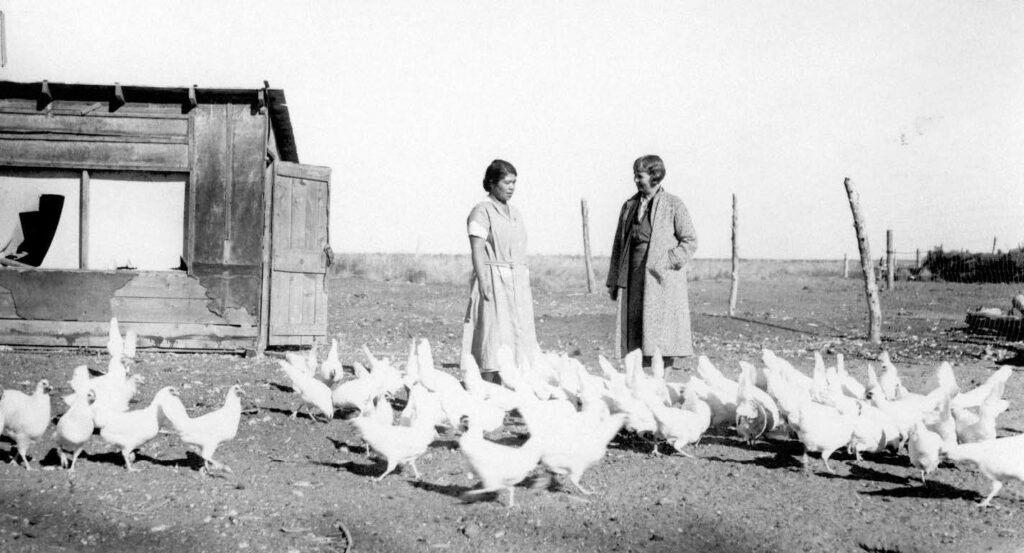

Photo courtesy National Archives and Records Center (NARA).

Bowler spent five of her most challenging and rewarding years as superintendent. She oversaw purchases of agricultural land for existing reservations and new Yomba, Duckwater, and Campbell Ranch Reservations. Much needed reservation houses were built to reduce chronic overcrowding and the spread of diseases.

Other actions focused on boosting reservation economies. The Indian Bureau offered loans to organized tribes for the formation of livestock cooperatives to buy and sell cattle and sheep. Native women were encouraged to “revive and perpetuate” traditional crafts to sell through the new Wai-Pai-Shone Craft Cooperative.

Vocational programs at the Indian School were expanded. Bowler was adamant that students graduate with marketable skills in the rural community. Training followed gender-specific norms of the times — nursing and domestic work for girls and farm mechanics and carpentry for boys.

The suffering on the reservations called for immediate action. Bowler’s impatience with the Washington Bureaucracy can be gleaned from selected letters to Commissioner Collier in 1936. After delays in receiving building plans, Bowler relied on the Indian School carpentry shop to prepare drawings for reservation housing. She shared her frustration: “It makes us a little sick to think how much help those [drawings] would have been had they arrived earlier.”

She became embroiled in two long-standing conflicts involving the threatened Pyramid Lake Fishery, and a decade-long dispute between the Pyramid Lake Tribal Council and five non-Indian families over disputed land and water rights on tribal land along the lower Truckee River. Fishing was a major source of food — and recently, income — for Northern Paiute people. Its sustainability had come into question. Overfishing and the U.S. Reclamation Service’s diversion of Truckee River water to the Newlands Project in Fallon led to major declines in fish populations. Low river levels and a silted-up Pyramid Lake delta inhibited the Cui-ui and Cutthroat Trout from active spawning. Bowler was angered by a 1935 Bureau of Fisheries report that blamed the Indians for mismanagement of the fishery.

A shortage of river water and irrigable land hindered the Pyramid Lake Reservation’s plans to expand its agricultural economy. For over seven decades, five white families, referred by some as “squatters,” farmed most of the premium land on the lower Truckee River. While some families chose to lease or purchase the Indian land; others did not. The Indian Bureau offered to purchase the settlers’ land (at Depression prices) but some families held out for more lucrative deals. The Bureau’s legal attempts to evict these families stalled due to the repeated ploys of the settlers’ legal counsel, Nevada’s U.S. Senator Patrick McCarran, who tried to secure free title for his clients.

Meanwhile, a resolute Bowler advised the Pyramid Lake Tribal Council to continue the fight to regain its land. Tempers flared and McCarran accused her of being prejudiced against himself and the settlers. Despite an outpouring of tribal support, the powerful senator pressured Collier into removing Bowler from her position.

Bowler voiced her optimism over the “larger opportunities” that awaited her and downplayed any sorrow she felt in a statement to the Nevada State Journal on November 2, 1939:

I do deeply regret having to leave Nevada. I have fallen in love with the State–its beauty, its climate, and its people—especially the Indian people. The work in the Carson Indian Agency for the past five years has given me a greater and more genuine satisfaction than any of the things I have tackled in previous years…. I have been privileged to serve as their advisor and friend.

Bowler left with a strong sense of accomplishment knowing that Nevada Indians made substantial steps toward achieving self-sufficiency and self-governance during her tenure. Bowler was transferred to the position of “Superintendent-at-Large” with headquarters in Los Angeles, California. She resided with her older sister Rilla in the suburb of Glendale.

As part of her new duties, Bowler would investigate special problems within the Indian Service administration and cover superintendent vacancies. In 1940, Commissioner Collier sent Bowler to Mexico to study their “ejido” system of communal farming and compare the Mexican credit system for Indians with the IRA’s credit system. She eventually left the Indian Service but would return. A 1950 U.S. Census shows her employed as a placement officer for the Navajo Service.

Arthur Rothstein photo courtesy of the National Archives and Records Center, San Bruno

Years later, insights into Bowler’s motives in the land dispute surfaced when reporter A.J. Liebling (New Yorker Magazine) interviewed her in southern California. When asked about McCarran’s accusation, she scoffed, “As if you could be too prejudiced in favor of the people it is your duty to protect.” Bowler admitted that Pyramid Lake leaders once dared her to do something about the settlers. She candidly confessed, “Being a woman, I imagine I felt under a greater obligation to show them.”

Bowler retired at the age of 65 and lived to the age of 81. She will be remembered for being a strong advocate and defender of Indian rights.

Researched and written by Renee Corona Kolvet. Posted December 2022. (Edited August 2023)

Sources of information:

- Ahlstedt, Wilbert Terry, “John Collier and Mexico in the Shaping of U.S. Indian Policy” 1934-1945.” PhD. Dissertation, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, May 2015. Accessed 7/10/2023 from digitalcommons.unl.edu/historydiss/82/

- Alida C. Bowler to Commissioner of Indian Affairs, June 9, 1936, Record Group 75, United States Bureau of Indian Affairs, Carson Indian Agency, Indian Relief and Rehabilitation, National Archives, San Francisco.

- Alida C. Bowler to Commissioner of Indian Affairs, December 15, 1936. Record Group 75. United States Department of Interior, Office of Indian Affairs, Field Office, on file, Stewart Indian School Cultural Center and Museum

- Alida C. Bowler to All Agency Personnel. “Memorandum, Arts and Crafts Program,” February 14, 1936. On file, Stewart Indian School Cultural Center and Museum.

- “Alida C. Bowler Receives Transfer.” Nevada State Journal, November 2, 1939, p. 12:1-2.

- Ancestry.com. Year: 1920, Census Place: Seattle, Washington; Roll: T625; Page 6B; Enumeration District 238. [Alida C. Bowler].

- Ancestry.com. Year: 1950, Census Place: Glendale, California; Page 4, Enumeration District 64-32, [Alida C. Bowler].

- Associated Press, “Woman Appointed to Govern Indians,” New York Times, August 4, 1934, p.13:1.

- Black, William G. “Social Workers in World War I: A Method Lost.” Social Service Review, Vol. 65, No. 3, September 1991: 379-402.2:1-2.

- Carey, Andrew W. “Questions of Sovereignty: Pyramid Lake and the Northern Paiute Struggle for Water and Rights (2016). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/anth_etds/79/

- Collier, John, From Every Zenith: A Memoir and Some Essays on Life and Thought. Denver: Sage Books, 1963.

- Collier, John C. to Alida C. Bowler, October 27, 1939. Record Group 75, United States Department of Interior, Office of Indian Affairs, National Archives, St. Louis, MO.

- Jordan, Angela, “University of Illinois Archives.” Alida Cynthia Bowler: Responsibility of Privilege. (April 11, 2014). https://archives.library.illinois.edu/blog/alida-cynthia-bowler/

- NWHP Biography Alida Cynthia Bowler Page 7 of 7

- Knack, Martha C. and Omer C. Stewart, As Long as the River Shall Run: An Ethnohistory of the Pyramid Lake Indian Reservation. Reno and Lake Vegas: University of Nevada Press, 1984.

- Kolvet, Renee Corona, “The Indian New Deal: Scenes from the Carson Indian Agency,” Nevada Historical Society Quarterly, Volume 54, No. 1-4, 2011: 3-48.

- Liebling, A.J., “A Reporter at Large, The Lake of the Cui-ui Eaters.” The New Yorker, January 22, 1955.

- Liebling, A.J., A Reporter at Large, Dateline: Pyramid Lake, Nevada. Ed. Elmer R. Rusco. Reno and Las Vegas, University of Nevada Press, 2000.

- Official Register of the United States, 1933, Department of Labor [database on-line], Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc. 2022.

- Rusco, Elmer R. “The Indian Reorganization Act in Nevada: Creation of the Yomba Reservation,” Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology, Vol.13, No. 1, 1991: 81.

- Rusco, Elmer R., A Fateful Time: The Background and Legislative History of the Indian Reorganization Act. Reno and Las Vegas: University of Nevada Press, 2000.

- United States of America, Passport Applications, 1795-1925, June 23, 1918 [database on-line], Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, inc. 2022.

- Williams, Samantha M., Assimilation, Resilience, and Survival: A History of the Stewart Indian School, 1890-2020. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2022.