Nevada Historical Society, Reno

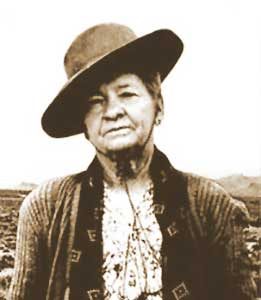

JOSEPHINE (JOSIE) REED PEARL

The information below has been compiled from a variety of sources. If the reader has access to information that can be documented and that will correct or add to this woman’s biographical information, please contact the Nevada Women’s History Project.

At A Glance:

Born: December 19, 1873

Died: December 29, 1962

Maiden Name: Reed

Race/Nationality/Ethnic Background: Caucasian

Married: Lane Pearl

Primary City and County of Residence and Work:

Goldfield (Esmeralda Co.), Cove Canyon (Humboldt Co.), Ward, Minerva (White Pine Co.)

Major Fields of Work: Mining (prospector, miner)

Other Role Identities: Wife, Boardinghouse Waitress

Josephine (Josie) Reed was born in Evening Shade, Arkansas on December 19, 1873 and lived long beyond her allotted three score and ten years. She became one of Nevada’s most notable characters. She and her family moved to Tennessee in 1875 and to San Luis Valley, New Mexico Territory, six years later. She loved being outdoors and developed an interest in mining in her early teens when shown how to pan for gold. In 1886 she filed a gold claim at Rat Creek which she later sold for $5,000.

Moving to Crede, Colorado in 1890, Josie worked as a waitress in a boardinghouse until she married a young mining engineer, Lane Pearl, two years later. For the next ten years, she followed him from one mining camp to another, and they ended up in Goldfield, Nevada in 1904. When Goldfield’s boom went bust in 1910, the couple moved to Ward in White Pine County. Josie continued to work in restaurants and boarding houses while also prospecting.

Following her husband’s death in 1918, she drifted from one end of Nevada to the other for the next four years. In 1922, she acquired several mining claims in the Columbia Mining District in the Pine Forest Range of northern Humboldt County and settled down for good, building a cabin in Cove Canyon near the Black Rock Desert where she was to remain for the next forty years.

For years she hoped to make a big strike, but her claims provided only the most meager living. Nonetheless, she grubstaked other prospectors, apparently hoping that their luck would be better than hers. However, it was not to be.

When writer Ernie Pyle visited her in 1936 and wrote a feature article about her in his nationally syndicated column, he described her as:

“…a woman of the West. Her dress was calico, with an apron over it. On her head was a farmer’s straw hat. On her feet a mismatched pair of men’s shoes, and on her left hand and wrist $6,000 worth of diamonds! That was Josie-contradictions all over, and a sort of Tugboat Annie of the desert. Her whole life has been spent hunting for gold in the ground. She was a prospector. She had been at it since she was nine, playing a man’s part in a man’s game.”

Pyle later became a famed war correspondent, losing his life in Okinawa in 1945. In 1947, selections from his columns were published in a book, Home Country, and Josie once again found herself on the national stage for a brief moment. However, other writers who wanted to follow up on Pyle’s story were either unable to locate her place or found the cabin deserted when they arrived.

In 1953, Western writer Nell Murbarger heard that Josie was still alive and was able to get directions to her camp. In an article which appeared in Desert Magazine in August 1954, Murbarger described her as “not a large woman, but healthy-looking and robust, with determination and self-sufficiency written all over her.” Her face was “one of the most unforgettable I have ever seen,” she wrote. “Years were in that face-a great many years-but there was in it some indefinable quality that far overshadowed the casual importance of age. The eyes that bored into mine were neither friendly nor unfriendly. Rather, they were shrewd and appraising; as steady as the eyes of a gunfighter; as noncommittal as those of a poker player.”

Pyle had described Josie’s cabin as “the wildest hodgepodge of riches and rubbish I’d ever seen,” a judgment Murbarger with which agreed. Josie kept letters from friends pinned on the walls, assay reports, newspaper clippings, tax receipts, piles of newspapers and magazines. Josie confirmed her grubstakes with other would-be mining magnates and told Murbarger of the many lawsuits she had been involved in over the years. Murbarger wrote:

“She also told of loneliness, of what it meant to be the only woman in mining camps numbering hundreds of men. She told of packing grub on her back through twenty-below-zero blizzards, of wading through snow and sharpening drill steel and loading shots, of defending her successive mines against high graders and claim jumpers and faithless partners.”

When she got lonely in later years, she would drive her pickup the seventy-five miles into Winnemucca to visit Avery Sitzer, editor of the Humboldt Star. When her eyesight began to fail, however, she became a menace to local ranchers and other drivers, coming hell-bent-for-leather down the middle of the road leaving clouds of dust in her wake. “Oh, oh, here comes Josie, head for the brush,” was the usual comment of those who knew her.

In the fall of 1962, she fell ill of heart disease and complications of old age and died at Washoe Medical Center on December 29. On her death certificate, her occupation was listed as “hardrock miner.” She was much more.

Biographical sketch by Phil Earl.

Sources of Information:

- Earl, Phillip. “Woman prospector settled down in Black Rock Desert.” Reno Gazette- Journal, November 22, 1993.

- Murbarger, Nell. “Queen of the Black Rock Country.” Sovereigns of the Sage. Tucson; Treasure Chest Publisher, 1958.

- Zanjani, Sally. A Mine Of Her Own. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1997.