The information below has been compiled from a variety of sources. If the reader has access to information that can be documented and that will correct or add to this woman’s biographical information, please contact the Nevada Women’s History Project.

At a Glance:

Born: June 13, 1937, Sabot, Goochland County, Virginia

Died: Feb. 9, 2021, Virginia City, Nevada

Maiden Name: Winston

Race/Nationality: African-American

Married: Melvin Parham, 1959; Stirling R. Bouldin Jr., 1977

Children: Tonya Parham

Primary City and County of Residence/Work: Virginia City, Storey County, Nev.

Major Fields of Work: Teacher, librarian, musician

Other role identities: Singer, mother

Northern Nevada librarian, musician met early racial discrimination

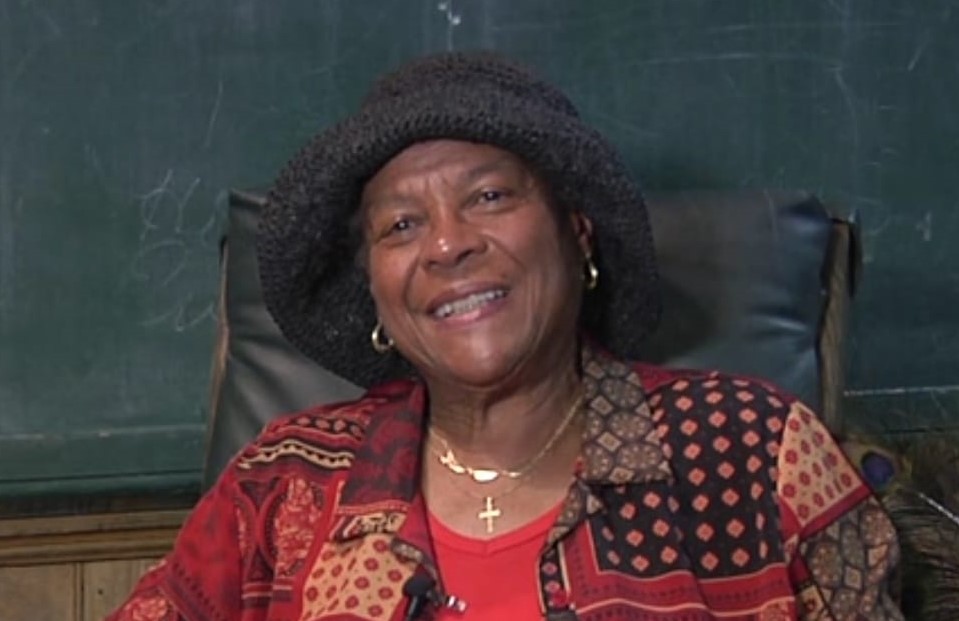

A teacher, singer, organist, librarian and mother, Lucy Bouldin was a well-known presence in northern Nevada and her native Virginia where, earlier in her life, African-Americans were still quite marginalized.

Born Lucy Anna Winston in the town of Sabot, Goochland County, Virginia, to Oliver A. and Bessie J. Winston, she came into this world with the help of her grandmother, a midwife who later delivered more than 2,200 babies. She went to segregated schools called “colored schools” in Virginia. One was a two-room elementary school with two teachers for eight grades. She credited those two teachers for inspiring her to do the best she could at everything. “Each generation has to move forward and do better,” she said in a 2014 interview.

She finished high school as valedictorian at age 15 and college at 20 with a degree from Virginia State College in vocal music education. She at first taught at her old high school and then at a school that later fired her and all 72 African-American staffers when the school decided it did not want to abide by desegregation and became an all-white private school instead.

Lucy moved to Berryville, Va., and it was there that she fell in love with Melvin Parham, who married her and moved her to Washington, D.C. She had her daughter Tonya there in 1960 and worked for the National Symphony Orchestra for two years before returning to teaching, this time in Prince George’s County, Maryland. There she made $300 less per paycheck than the white teachers she worked with. She was an “integration hire” and taught music and physical education at two elementary schools.

She liked to remember two stories from those days: One involved a parent seeing her in the playground one day and exclaiming “Oh, my god, that’s a (N-word). What is she doing there?” Bouldin said that fortunately she was in a good mood that day, so she said, “Where? Where?” The parent didn’t know what to say to that, and it was never brought up again.

Another involved a child telling her she’d seen Bouldin’s car at the grocery store but was surprised because a “colored man” was driving it. When Bouldin told her it was her husband, the child said, “No, it was a colored man.” Bouldin later recalled, “At that point I realized that once she had gotten to know who I was, then I was no longer colored. I was like her. I was finally able to convince her that no, it had not been stolen, but was being driven by my husband.”

She retired from Prince George County in 1987 on Juneteenth, the day that honors the emancipation of Black Americans and was just made a federal holiday in 2021. She was by then married to Stirling Bouldin, who wanted to move to a place where they’d pay less taxes than they did in Maryland and would be able to gamble more, an activity they both enjoyed. They had traveled to Nevada several times, including to Reno where they had married in 1977. After ruling out Elko (“They didn’t have an airport and we love to travel”) and Las Vegas (“It was basically one season”), they bought property and built a house in Virginia City Highlands. The Storey County School District was short of substitute

teachers, so she was asked to teach there in February 1978. One day the superintendent asked if she could “temporarily” supervise the new Storey County library, which was being located in a new high school. That temporary job ended up running from 1989 to 2012.

Lucy’s husband Stirling died in September 1989. He had been a cab driver for 40 years and a volunteer firefighter in the Virginia City Highlands.

In a lengthy interview for “Women of Diversity: Nevada Women’s Legacy,” part of a project celebrating Nevada’s sesquicentennial, Bouldin said her most famous student over the years was probably a shy young man in Virginia named Sugar Ray Leonard, the now-famous boxer and motivational speaker.

Other personages she had met: “I enjoyed having fights, at my hairdresser, with a certain person, because we had the same hairdresser.

My hairdresser’s name was Maymie Durham. And the person I could fight with on occasion was Maya Angelou.”

She also called herself not an optimist nor a pessimist, but a “factualist, not looking at everything as good or bad, but as what it is now.”

In addition to her teaching and library work, Bouldin often sang and played organ for the community or at churches. She performed at such diverse events as a reception for the Nevada State Library and Archives in Carson City, “The Vietnam Wall Experience” in Reno, the Reno/Sparks NAACP Freedom Fund Banquet, and the Nevada Day Parade on a Women’s Suffrage float. Since she considered the Episcopal Church central to her life, she played organ for 11 years at St. Paul’s Episcopal in Virginia City and at Trinity Episcopal in Reno. She sang in the Carson City Chamber Singers for many years as well.

Lucy Bouldin died at the age of 83 on February 9, 2021, at her home. She was buried next to her husband in Virginia City. Her daughter, Tonya Parkham, is a retired U.S. Air Force Captain.

Researched by Mona Reno and written by Kitty Falcone

Posted July 29, 2021

Sources of Information

- Adrian, Marlene J., Gerdes, Denise M. (Eds.), “Lucy W. Bouldin, Factualist,” in Storey County. Nevada Women’s Legacy-150 Years of Excellence (pp. 89), Women of Diversity Productions Inc., 2014.

- Ancestry.com. Virginia Department of Health; Richmond, Virginia; Virginia, Births, 1864-2016.

- Ancestry.com. Virginia Department of Health; Richmond, Virginia; Virginia, Marriages, 1936-2014; Roll: 101169299.

- Ancestry.com. Nevada, U.S., Marriage Index, 1956-2005. Provo, Utah, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2007.

- “Group celebrates women’s role in history.” Reno Gazette-Journal (Reno, Nevada), November 12, 2014, p. B6, col. 6.

- “Lucy W. Bouldin, Factualist, Full Length Interview.” Nevada Women’s Legacy Interviews, Women of Diversity, Productions Inc., Las Vegas, Nevada. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P2MMg1JsftI Retrieved April 9, 2021.

- “Photos of African-Americans in Nevada history go on display.” Reno Gazette-Journal (Reno, Nevada), February 5, 1998, p. 57, col. 4.

- “Remembering Chamber Singer Lucy Bouldin, February 9, 2021,” Carson City Symphony Home Page. Retrieved April 9, 2021.

- “Rights group praises new century of progress.” Reno Gazette-Journal (Reno, Nevada), May 14, 2000, p. 25, col. 2.

- “Saloon excavation provides insight in how blacks lived on Comstock.” Elko Daily Free Press (Elko, Nevada) August 19, 2000, p. 4, col. 3.

- “Stirling R. Bouldin Jr.” Reno Gazette-Journal (Reno, Nevada), September 6, 1989, p. 28, col. 1.

- “‘The Wall’ That Heals.” Reno Gazette-Journal (Reno, Nevada), July 12, 1998, p. 39, col. 5.

- “Virginia City.” Reno Gazette Journal (Reno, Nevada), January 28, 1990, p. 18, col. 5, Section: Storey County.